2024. What factors make it hard to predict the behaviour of a system and what are the implications for AI safety?

In what follows, I consider challenges to the goal of predicting the behaviour of AI systems. The questions of how and whether this goal can be achieved are central to AI safety. I will present my thoughts in response to Dalrymple and colleagues’ (2024) paper on guaranteed safe AI (GS AI). This new framework is aimed at creating quantitative guarantees of AI systems’ safety. The framework has three key components: a world model, which is a description of how the AI system affects the world, a safety specification, which describes what behaviour is acceptable, and a verifier, which is to offer a verifiable proof certificate that the AI meets the safety specification with respect to the world model. Both the world model and safety specification are to be expressed mathematically, and the world model needs to have predictive power. They write that “All potential future effects of the AI system and its environment relevant to the safety specification should be modelled (and – if feasible – conservatively over-approximated) by the world model” (Dalrymple et al., 2024, p. 4).

This is a tall order, but it has the important advantage that it highlights what is needed for a quantitative guarantee of an AI system’s safety:

Any strategy for creating safe AI systems must rely on some beliefs or assumptions about the real world, and these assumptions could be wrong; a world model simply makes these assumptions explicit. Stated differently, if it is impossible to create world models that are sufficiently accurate to ensure that an AI system adheres to some specification, then it is presumably in general impossible to ensure that this specification is satisfied by that system. (p. 8)

The GS AI approach includes different degrees of safety, and allows for probabilistic specifications, models, and guarantees. I will outline reasons why quantitative safety guarantees may be difficult to achieve for certain types of AI systems. Specifically, I will focus on the world model and the difficulty of predicting the future effects of AI systems.

Combinatorial spaces and horizons of predictability

To model how a system will behave and unfold over time, one must have some means of modelling the system’s space of possible configurations. A light switch may be on or off. The possible game states of tic-tac-toe, played on a 3×3 grid, number in the thousands. Claude Shannon (1950) roughly estimated that chess, played on a 8×8 grid, have around 1043 possible positions.

Stuart Kauffman (2016) gives the example of all possible proteins made with 200 amino acids. There are 20 different amino acids, which means that there are 20200 possible proteins of amino acid length 200. In his calculation, if all of the 1080 particles in the known universe did nothing except make proteins of length 200 every Planck moment (10–43 seconds), it would take around 1039 times the lifetime of the universe to produce all the possible proteins of length 200, once (Kauffman, 2016, p. 66). The average protein has about 300-400 amino acids. In other words, there is a combinatorial explosion of possible proteins and, by analogy, of possible DNA sequences, organs, and species. One might counter that the actual number of viable proteins is much smaller than the total number given above. The difficulty in saying how much smaller, i.e. how many viable proteins there are, illustrates the point.

Similarly, societies are composed of re-combinable customs, roles, beliefs, institutions; technologies are composed of re-combinable functional subcomponents, parts, and materials; texts are composed re-combinable words and sentences; plans are composed of re-combinable actions and subgoals. Language, in this way, is not unique in enabling the “infinite use of finite means.” The point is not that systems like organisms or societies can be reduced to loose collections of reconfigurable parts—there are strong structural, physical, and functional constrains in biological and social evolution (Gould, 2002; Hallpike, 1986). The point is that certain systems have combinatorially large spaces of possible configurations, which makes it hard to predict how such systems will unfold.

When we observe the biosphere at one point in time, we can make educated guesses about how things will unfold in the near future. We can say: given predation pressure X, food abundance Y, or soil composition Z, population A, B, or C is likely to expand or contract. To use Kauffman’s term, we can predict the adjacent possible. The more distant future, of new species and ecosystems, we cannot predict. One fundamental reason why we cannot predict this is that we do not know the space of possible species or ecosystems.

Three other reasons why systems can be hard to predict are that the rules, constraints, or mechanisms are imperfectly understood, the role played by incidental and random factors, and imperfect measurements. For example, knowing physiological and neural mechanisms is essential to predict the effects of drugs. Prediction is made hard by incidental and random factors, such as random mutation in cells’ DNA and the role of initial conditions in weather patterns (Gleick, 1998).[1] The development of organisms is noisy (Lewontin, 2000), it would be strange if the same were not true, at least to some extent, for the growth and development of AIs. Imperfect measurements is not a minor difficulty. If I had a precise and accurate theory of how people’s mental states interacted to produce social change, I could not use this theory to predict social change unless I could define the relevant mental states and then invent the tools to measure them accurately.

In chaos theory, the time limit beyond which the behaviour of a system cannot be predicted is called the horizon of predictability. This concept applies well to the challenge of modelling the future effects of an AI system, the environment in which the AI operates, and the interaction between the two. Based on the preceding discussion, the following are four important factors—veils—shortening and clouding a system’s horizon of predictability:

- a large combinatorial space of possibilities;

- imperfect understanding of the system’s rules, constraints, and mechanisms;

- influence of random or incidental events;

- imperfect measurement.

To make these veils more concrete, I will apply them briefly to the question of whether we can predict the future behaviour of Language Models (LMs).

Predicting LMs

When an AI lab pretrains a new LM, they do not know the full space of possible representations and skills that the AI model will gain from the training process. The empirical tendency for token prediction accuracy to improve as model size, compute, and training data are scaled gives the lab some limited ability to predict how the model will perform, but the so-called “scaling laws” have not enabled people to predict ahead of training the emergent abilities of LMs, such as in coding and reasoning (Ganguli et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2022; Wei, 2023). LM abilities are mostly explored and mapped after training, not predicted before training.

For developers to better estimate the space of possible LM representations and skills, our understanding of the rules, constraints, and mechanisms of machine learning will have to improve considerably. The complete lack of consensus on how far we are from creating AGI, whether AGI is achievable using current transformer architectures, and even what AGI means, is testament to our lack of understanding of which architectures, training algorithms, and data can enable AI models to learn which representations and skills.

LMs are also sensitive to noise, whereby seemingly insignificant aspects of a prompt can change model output, sometimes significantly (Salinas & Morstatter, 2024; Sclar et al., 2023). In one case, Ullman (2023, p. 3) found that GPT-3.5’s response to a theory of mind task was altered by the presence of a double space in the prompt. Another source of noise is the massive training data that models are fed. By training models on datasets so large that it becomes prohibitively expensive to map and categorize their contents, developers lose the opportunity to gain a better understanding of which data help teach the large models which skills.

Finally, our ability to define and measure LM representations and skills is currently limited, although it is progressing. Anthropic researchers were able to extract some interpretable features from the middle layer of Claude 3.0 Sonnet (Templeton et al., 2024). The features correspond to concrete and abstract entities, such as specific people, the Golden Gate Bridge, and scientific fields. This line of research holds promise, but it is currently far from being able to tell us how models manipulate representations and solve reasoning tasks. Moreover, our lack of understanding of how the models reason make it difficult to characterize their abilities based on performance on various benchmarks (Geirhos et al., 2023). The debate about to what extent LMs memorize or generalise is very much open (Mitchell and Krakauer, 2023; Bubeck et al., 2023; McCoy et al., 2023).

For these reasons, LMs are currently not robustly predictable. The degree of predictability that does exist is based on our empirical exploration of the models, not well-established theory. People were able to jailbreak ChatGPT within the first day of its release, showing how short the horizon of predictability can be when a poorly understood system is released in an open-ended environment.

The four veils help highlight what is needed to make LMs more predictable. First, a better understanding of the space of possible representations and skills that can be learnt from what architectures, algorithms, and data would enable developers to better forecast what their models can do. This, along with a framework for mechanistically measuring, or at least identifying, representations and skills in LMs, would strengthen our ability to understand the space of possible model behaviour. Finally, the LMs need to be made robust to noisy and variable inputs, such that model safeguards also work when jailbreaks are attempted using out-of-distribution methods. In an interview, Demis Hassabis made a relevant point about the challenges posed by generative systems:

… if it was a normal piece of software, you could say I’ve tested 99.999% of things, so then it extrapolates … But that’s not the case with these generative systems. They can do all sorts of things that are a little bit … out-of-the-box, out of distribution. If someone clever or adversarial decides to … push it in some way … it’s so combinatorial, it could even be with all the things that you’ve happened to have said before to it. And then [the AI] gets into some kind of peculiar state, or it’s got its memories filled up with a particular thing, and that’s why it outputs something. So there’s a lot of complexity there, but it’s not infinite. (Hassabis 2024)

Even if the complexity is not infinite, the space of possible human inputs—benign or malign—to AI systems is extremely large.

Unpredictable AI systems

Taking for granted that to model the future behaviour of an AI system, we need to be able to understand it and measure its abilities to some degree, what are properties that would make an AI system difficult to predict, even if we understood it? Two properties stand out, both of them related to the four veils discussed above. First, an AI system with chaotic properties, where the change in its mental states were sensitive to training data noise, initial conditions, and perturbations, would be unpredictable in some respects.[2]

The second and most important property, is creativity. It is a somewhat nebulous property. Here, I take creativity to be the ability to form new concepts or actions by decomposing known patterns into subcomponents or abstract units and flexibly recombining them to form new and original concepts or actions. It can be done deliberately, for example through creative search, and as a byproduct of learning. It relies on what Lake et al. (2017) call compositionality, where

… an infinite number of representations can be constructed from a finite set of primitives, just as the mind can think an infinite number of thoughts, utter or understand an infinite number of sentences, or learn new concepts from a seemingly infinite space of possibilities. (p. 14)

Creativity, in a sense, is the ability to explore a combinatorial space of possibilities. Conceptual creativity is particularly relevant here, as the ability to form new concepts can greatly facilitate other kinds of creative activity. Having a richer conceptual framework expands the space of possible thoughts, plans, and actions. In this context, open-ended learning of new concepts is a form of conceptual creativity.

If an AI system of some degree of general intelligence had the ability to creatively modify its own mental models, it seems to me that such a system would be extremely difficult to predict. To model the future behaviour of such a system, one would have to model the space of possible concepts that the system could acquire. However, the reason why this is difficult is precisely the reason why we would want to create such a system: we want it to help us understand things we do not already understand and solve problems we currently cannot solve. This gets to the tension at the heart of the ambition to create superhuman AI systems. We want them to do and think things we cannot, but in creating such systems, how can we know what they will do?

LMs are sometimes criticised for not being able to do live learning, i.e. to learn continually while in operation and interaction with users, as opposed to in training. For safety and prediction purposes, however, that is one of LMs’ main qualities. It is a difficult challenge to try to understand how LM training gives rise to their capabilities. But training and fine-tuning at least involve creating a somewhat fixed system, whereas a similarly capable AI system that could continually learn from its interaction with users and the environment would be much harder to predict and study. Here, it may be useful to distinguish between generative creativity and the ability to learn from one’s creativity. LMs have generative creativity. In interaction with a human, LMs can generate new ideas. Unlike humans, an LM cannot integrate into itself the new ideas it produces or studies. The reason creativity is useful to us is that we can learn from and integrate the creative products we like or find helpful. LMs cannot do this, but an AI system that could, would potentially be more powerful and less predictable.

Further challenges to prediction

Dalrymple et al. (2024) acknowledge the difficulties facing their approach. They point to the challenges in formally defining safety-relevant notions such as harm and causation. They note that powerful AI models are likely to shape their own use context, making it hard to make strong assumptions about the future inputs to such systems. Humans are likely to be a central part of the environment with which AI systems interact with. In that regard, they write that the world model will need to model the behaviour of humans. Humans being complex creatures, they argue that

it seems dubious to presuppose that it is possible to create a model of human behaviour that is both interpretable and highly accurate (especially noting that such a model itself would constitute an AGI system). There may thus in some cases be a fundamental trade-off between interpretability and predictive accuracy. (p. 8)

But how far does this tradeoff take us, with humans or with AIs? Even if we were willing to trade all interpretability for maximum predictive accuracy, would the hypothetical black box predictive models get us near where we would want to be to rely on their predictions to deploy a powerful AI system? Do we have well-founded reasons, in principle, to think that hypothetical predictive models, interpretable or not, can predict all future safety relevant actions of humans and AIs (that mutually interact)? Proving that a black box AI system A is safe and then use that system predict that another system B is safe, only works on the assumption that black box system A can persistently capture the potential safety-relevant actions of system B. If, however, system B can change and form qualitatively new concepts or actions, system A’s predictions will no longer be reliable.

Responding to the potential argument that the GS AI agenda may fail to work in a world too complex to be accurately captured by a world model, Dalrymple et al. argue that model uncertainty can be taken into account in the verification, thereby making the guarantee “appropriately sensitive to the reliability of the world model” (p. 8). This, however, depends on one’s ability to reasonably quantify the relevant uncertainty. A probabilistic estimate of a world model’s reliability relies on an assumption of stability in the relationship between the model and the distribution of real-world data, inputs, and outputs that the model aims to capture. In a bounded environment, this assumption may hold. However, as Dalrymple et al. (2024) write, “the usage of powerful AI is likely to itself create situations that are novel and unprecedented … Stated differently, we should assume that “distributional shift” will occur” (p. 4).

Is alignment a puzzle?

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas S. Kuhn (2012/1962) wrote that “one of the things a scientific community acquires with a paradigm is a criterion for choosing problems that, while the paradigm is taken for granted, can be assumed to have solutions” (p. 37). In Kuhn’s terminology, such problems are called puzzles. Is alignment a puzzle? Despite the absence of a scientific paradigm that can explain or could predict the success of state of the art language models, alignment is often talked about as if it were a puzzle. Framing alignment as a puzzle—implying that it has a solution, however hard it may be to find—can help motivate alignment researchers for the same reasons that puzzles motivate scientists in general. However, it might mislead by giving the false impression that we know that a general solution exists. The space of possible AI systems is, for all we know, infinite. The task of aligning the subset of them that we can build most likely requires system-specific approaches. When someone talks about failure to “solve alignment”, imagine a doctor apologizing to her colleagues that she could not “solve disease”. One broader way of thinking about alignment is outlined below.

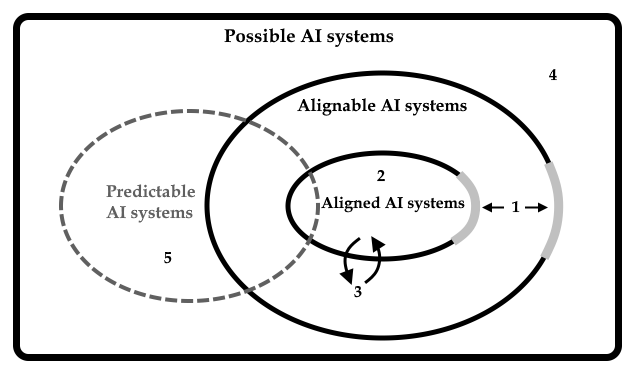

The figure highlights five important but not exhaustive tasks. First, we must try to determine what we consider to be the characteristics of aligned AI systems and which systems are possible to align by those standards. The grey zones of the boundaries emphasize that our criteria of alignment are likely to contain grey areas. It is important to figure out where these grey areas are and not to wander around in them if the stakes are high. Second, there is the technical challenge of building aligned systems. If an AI system operates over longer timeframes, learns, and changes, we will be faced with a third challenge: to prevent aligned systems from becoming misaligned and to realign misaligned systems. The latter is only possible if the AI system is not more powerful than us. This reminds one that building a plastic superhuman AI system is a potential one-way ticket to misalignment, even if the ride is smooth at first.

Fourth, we must actively refrain from building systems that we have reason to think are not possible to align by our standards. This is not a technical challenge, but a social, political, and moral one. Whether we succeed in our attempt to live with advanced AI systems will, I believe, be determined in greatest proportion by what we decide not to do.

Fifth, we need to improve our ability to predict AI systems, through improving our understanding of them and by designing systems that are predictable. The figure points to an open question: are the subset of AI systems that are alignable also predictable? To what extent do these groups overlap, or, how important is prediction to alignment? This is an important open question. For narrow systems, unable to interact with and learn from open-ended environments, prediction of their behaviour could be the most useful safety approach. For reasons outlined here, the horizon of predictability might be short for other types of systems. AIs we do not understand well and cannot measure accurately, that exhibit random or chaotic behaviour, that interact with open-ended environments, and that are creative live learners, pose challenges to a predictive approach to safety.

Highlighting the problems can hopefully suggest paths to solutions. Obviously, improving our scientific understanding of AI systems will be helpful. Learning how to limit the potential influence of randomness or chaotic behaviour in AI systems will also be helpful. Dealing with creative and live learning AI systems in open-ended environments seems to be a particularly difficult task. Yet, creativity and learning is not magic, and a better understanding of how biological and artificial neural networks learn and what they are able to learn, for example, can help us better estimate the bounds of a particular system’s creativity or intelligence. A slightly different but complimentary approach to modelling all the future safety-relevant effects of an AI system would be to focus on what the system cannot do. If our understanding of how machines learn becomes more advanced, we might be in a position to know that a given system cannot acquire certain safety-relevant skills, even if we cannot predict the full breadth of the system’s future safety-relevant actions.

[1] The terms incidental and random are not meant in an absolute sense, but relative to the theory used for prediction. For example, while an extremely large variety of factors shape human development, developmental psychology can only deal with a few of them at a time. Necessarily, most of the minute details of a child’s life are incidental, from a theory’s perspective, to the child’s development.

[2] Very simple systems, such convection rolls or double pendulums, have chaotic properties. It has also been proposed that the human brain exhibits chaotic behaviour (Skarda & Freeman, 1987). Chaos does not mean that we cannot predict anything about the system’s behaviour; it simply places limits on what we can predict about those aspects of the system that behave chaotically.

References

Bubeck, S., Chandrasekaran, V., Eldan, R., Gehrke, J., Horvitz, E., Kamar, E., … & Zhang, Y. (2023). Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early Experiments with GPT-4. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.12712.

Dalrymple, D., Skalse, J., Bengio, Y., Russell, S., Tegmark, M., Seshia, S., … & Tenenbaum, J. (2024). Towards Guaranteed Safe AI: A Framework for Ensuring Robust and Reliable AI Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.06624.

Ganguli, D., Hernandez, D., Lovitt, L., Askell, A., Bai, Y., Chen, A., … & Clark, J. (2022). Predictability and surprise in large generative models. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 1747-1764).

Geirhos, R., Jacobsen, J. H., Michaelis, C., Zemel, R., Brendel, W., Bethge, M., & Wichmann, F. A. (2020). Shortcut learning in deep neural networks. Nature Machine Intelligence, 2(11), 665-673.

Gleick, J. (1998). Chaos: Making a New Science. Vintage.

Gould, S. J. 2002. The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard University Press.

Hallpike, C. R. 1986. The Principles of Social Evolution. Clarendon Press, OUP.

Hassabis, D. (2024). Unreasonably Effective AI with Demis Hassabis. Interview by Hannah Fry. DeepMind: The Podcast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZybROKrj2Q&t=1565s

Kauffman, S. A. (2016). Humanity in a Creative Universe. Oxford University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (2012/1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 4th edition. The University of Chicago Press.

Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. (2017). Building achines that learn and think like people. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40.

Lewontin, R. (2000). The Triple Helix: Gene, Organism, and Environment. Harvard University Press.

McCoy, R. T., Yao, S., Friedman, D., Hardy, M., & Griffiths, T. L. (2023). Embers of autoregression: Understanding large language models through the problem they are trained to solve. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.13638.

Mitchell, M., & Krakauer, D. C. (2023). The debate over understanding in AI’s large language models. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(13), e2215907120.

Salinas, A., & Morstatter, F. (2024). The butterfly effect of altering prompts: How small changes and jailbreaks affect large language model performance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.03729.

Sclar, M., Choi, Y., Tsvetkov, Y., & Suhr, A. (2023). Quantifying Language Models’ Sensitivity to Spurious Features in Prompt Design or: How I learned to start worrying about prompt formatting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.11324.

Shannon, C. E. (1950). Programming a computer for playing chess. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 41(314), 256-275.

Templeton, A., Conerly, T., Marcus, J., Lindsey, J., Bricken, T., Chen, B., Pearce, A., Citro, C., Ameisen, E., Jones, A., Cunningham, H., Turner, N. L., McDougall, C., MacDiarmid, M., Tamkin, A., Durmus, E., Hume, T., Mosconi, F., Freeman, C. D., Sumers, T. R., Rees, E., Batson, J., Jermyn, A., Carter, S., Olah, C., & Henighan, T. (2024). Scaling Monosemanticity: Extracting Interpretable Features from Claude 3 Sonnet. Anthropic. https://transformer-circuits.pub/2024/scaling-monosemanticity/index.html

Wei, J. (2023). Common arguments regarding emergent abilities. May 3rd, 2023. jasonwei.net. https://www.jasonwei.net/blog/common-arguments-regarding-emergent-abilities

Wei, J., Tay, Y., Bommasani, R., Raffel, C., Zoph, B., Borgeaud, S., … & Fedus, W. (2022). Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682.