2021. When and why did two of the most monumental inventions in world history take place? In this dissertation, I attempted to understand what shaped the invention of the watermill and the steam engine, and what factors generally contribute to technological growth.

E.F. Skinner, the making of steel using a Bessemer converter. CC. Original image.

- I. Introduction

- II. Theoretical Framework

- III. Changes in energy technology

- IV. The social world – economics and culture

- V. Technology and its transmission, the longue durée

- VI. Conclusions

- VII. Bibliography

I. Introduction

There is no economic law that postulates that the next three decades must mirror the last three. Much depends on what happens in technology and how people adjust. (Frey 2019, 298)

These lines, taken from Carl Benedikt Frey’s The Technology Trap, are illustrative of an attitude towards technology that has become prevalent in our period. Technology is seen as a force for change, a force almost outside human control, as implied by people having to “adjust” to “what happens in technology,” forgetting that technology itself is adjusted by people (at least for now). Individuals, companies, classes, nations, and even unions of nations must adjust to this force. The European Union states that “Investing in research and innovation is investing in Europe’s future. It helps us to compete globally and preserve our unique social model” (European Union 2021). In other words, the EU must keep up with the force of technology lest it risks to lose its future, its ability to compete, and its “social model.”

Isaiah Berlin, in an essay on nationalism, noted how the momentous transformations of European life, in terms of science, technology, new modes of production, the rise of states and classes, etc., contributed to a new historical consciousness in the 19th century. As he put it, the transformations “made men acutely conscious of change and excited interest in the laws that governed it” (Berlin 1972, 11). This thesis springs from the same consciousness of change, technological change, and an excited interest in its history and dynamics. By undertaking a historical comparison of technological development in ancient Greece and industrializing Britain, this thesis does not hope to discover “laws,” but perhaps some interesting patterns and lessons that may be useful in evaluating our current situation.

The subject of technology in these periods is vast, and we will therefore narrow our focus to a particular issue. In this thesis, we will be concerned with factors that conduce to technological innovation and growth. We will compare ancient Greece, long thought to be technologically stagnant, with industrializing Britain, famous precisely for its rapid technological change. The two areas and periods are interesting to compare for their similarities and differences. They are both considered important and transformative periods in European history; the ancient Greeks for their philosophy and democracy, and the British for their liberalism and industrial transformation. Moreover, they were both the originators of crucial changes in energy technology which later spread to the rest of the world. The Greeks, it seems from the sources currently available, invented the watermill, and the British were the main inventors of the modern steam engine. Because of their importance, this thesis devotes particular attention to these two inventions.

We will begin by a theoretical consideration of the causes of technological change, and proceed to discuss the invention of the watermill and the steam engine. We will then explore the social environment of technology, in terms of economics and culture. Finally, we will adopt a longue durée perspective before summarizing and concluding our analysis.

II. Theoretical Framework

Technology is a canvas upon which many interpretations, eulogies, and laments have been painted. To make clear what this thesis considers to fall within the frame of technology, it may be helpful to offer a working definition. Technology is here considered as that which makes possible or facilitates the achievement of the purposes of humans by the creative use of the external environment. The term creative does not imply an artistic purpose or impulse, although that might often be present, but the fact that humans appear to be the only creature that change, break apart, and put together their environment in comparatively free and non-bounded ways. As Vaclav Smil writes:

Although some primates—as well as a few other mammals (including otters and elephants), some birds (ravens and parrots), and even some invertebrates (cephalopods)—have evolved a small repertory of rudimentary tool-using capabilities, only hominins made toolmaking a distinguishing mark of their behavior. (2018, 6)

This, then, is the first premise of our analysis: that technology is an intimate part of human existence. Naturally, technology must have had some form of beginning, but the chicken-and-egg question of which came first, humans or technology, may not be reconcilable with the shared evolutionary history of humans and technology (Harari 2014, ch. 1).

Although it may be said that the human is a tool-maker, that does not tell us very much about what kind of tools and technologies specific humans make, or for what purpose they make them. To examine this, humans must be studied in their specific social and material environment, i.e., in a particular place among particular people. All societies creatively use their environment, whether it is for survival, comfort, or some other purpose, but what factors cause some periods and societies to witness more rapid technological change than others? To address this, we will begin by considering the reproduction and transmission of technology.

In order to maintain its technological level, and by implication its standards of living and consumption, a society needs to transmit to the next generation – reproduce – its technological knowledge. This can be done in many ways, such as master-apprentice relationships, societies of arts or crafts, books and technical manuals, universities, corporations, and so on. The society also needs access to the material demands of its technologies, and may be forced to change technology if the materials are no longer available for the existing technology to satisfy the demand for its output.

The reproduction of technological knowledge is discussed well in Joel Mokyr’s The Gifts of Athena, where he outlines a “theory of useful knowledge.” Mokyr makes a distinction between what he calls “propositional knowledge,” which is “what” knowledge (beliefs) about “natural phenomena and regularities,” and “prescriptive knowledge,” which is “how”knowledge about ways to “manipulate nature” (2005, 4, 10). The former, he calls Ω-knowledge, episteme; the latter, λ-knowledge, techne. One of Mokyr’s core arguments is that the expansion of a society’s total propositional knowledge, what he calls “set Ω,” and its increased accessibility to the general population, opens doors to more and better technologies.

An important concept that Mokyr introduces in this regard is the “cost of access to knowledge”:

Although knowledge is a public good in the sense that the consumption of one does not reduce that of others, the private costs of acquiring it are not negligible, in terms of time, effort, and often other real resources as well. (2005, 7)

Knowledge can, and perhaps ought, to be a public good, but it is not necessarily so in all cases. Knowledge considered in the abstract is a non-rivalrous good, but the use of knowledge can often take place under highly rivalrous circumstances. In a competitive economic system where different productive units compete based on price, quantity, quality, or design, technological knowledge will often be treated as a private good, such as trade secrets. While the sharing of knowledge can help technologies spread, private competition based on technological knowledge can also be a powerful stimulant to the development of technology.

“Technologies of access,” as Mokyr (2005) emphasizes, are key to understanding a society’s capacity to transmit its technological knowledge, whether to its new generations or to neighbouring or future societies. Mokyr mentions inventions such as written scripts, paper, and printing, and these are key breakthroughs that have facilitated and cheapened the transmission of knowledge. Moreover, low access costs also help make research and invention cumulative rather than repetitive; “the search for new knowledge will be less likely to reinvent wheels” (Mokyr 2005, 8).

On the importance of culture, Mokyr makes the following case:

Hellenistic civilization created Ptolemaic astronomy but never used it, apparently, for navigational purposes; nor did their understanding of optics translate into the making of binoculars or eyeglasses. What matters, clearly, is culture and institutions. Culture determines preferences and priorities. All societies have to eat, but cultural factors determine whether the best and the brightest in each society will tinker with machines or chemicals, or whether they will perfect their swordplay or study the Talmud. (2005, 18)

The example of Hellenistic civilization is unfortunate, as Ptolemaic astronomy was indeed used for navigation and their optics was put to the important function of extending the range of lighthouses (Russo 2004, 112, 116-7), but the point remains, culture shapes preferences and priorities. Simply put, a society that scoffs at its artisans and craftsmen is unlikely to develop new technology as fast as one in which they are respected. The social status of the inventor or tinkerer is therefore an important question. For example, is the inventor seen as a prophet of progress, or a disturber of the peace?

Finally, we turn to surplus produce. Increased surplus produce, by enabling more people to be engaged in non-agricultural production, is likely to contribute to the growth and improvement of a society’s technology. A society struggling at subsistence level production is unlikely to provide a surplus necessary to feed artisans and craftsmen, much less a class of inventors. On this issue, Alfred N. Whitehead, the philosopher and historian of science, makes an interesting comment:

“Necessity is the mother of invention” is a silly proverb. “Necessity is the mother of futile dodges” is much nearer to the truth. The basis of the growth of modern invention is science, and science is almost wholly the outgrowth of pleasurable intellectual curiosity. (1997, 140)

There may perhaps be agricultural innovations in a society on the margins of subsistence, but precarity would likely make farmers risk averse; you do not experiment with new forms of crop rotations if failure means your death. The distribution of surplus, however, is a political question, and a ruling class in a society may enjoy a substantial surplus with all its fruits of power, time, and leisure, while the lower classes of workers, slaves, or servants struggle to get by.

Once the surplus is accumulated, whether it be in the hands of a bourgeoisie, a priestly class, or a royal house, how it is used is a key question. It can be spent on bread and circuses, on lush ceremonies, on war, and so on, but if it is spent with the aim of fostering invention and innovation, it may be an extremely powerful force for technological change.

A final point on increased surplus produce is that it may not only be the cause, but also the effect, of technological development. Just like there may be vicious cycles in the case of surplus decline and technological decline, so there is virtuous cycles of increased surplus and technological growth. There have been theories put forth suggesting a minimum rate of investment in order to undergo an economic “take-off,” but the factors shaping virtuous or vicious cycles of economic investment and growth are more complex than can be modelled by a simple ideal rate of investment (Musson 1972, 42-3). A virtuous cycle may be ushered in by a farsighted monarch, but then aborted when the royal patron of the arts is deposed.

III. Changes in energy technology

In this section we will discuss energy technology in ancient Greece and industrializing Britain. Energy, as Smil writes, “is the only universal currency: one of its many forms must be transformed to get anything done” (2018, 1). In this sense, energy encompasses virtually everything humans do consciously or unconsciously. For the purposes of this thesis, however, energy technology refers to the ways in which humans use the environment to generate energy to power fundamental economic processes, ranging from the grinding of grain to the heating of metals. Smil emphasizes the human dependence on photosynthesis and its resulting phytomass (“plant biomass”), but since the dawn of civilization humans have become dependent on many other forms of energy conversions. Fundamental energy technologies, those that make energy available in general forms that can be put to various uses, are called “prime movers”. In this section, we will examine and compare two cases of the emergence of prime movers, namely the rise of water power and steam power.

III.I The watermill

It is generally agreed that the watermill was a Greek invention, although the exact dating is subject to some debate. The waterwheel may have been a slightly earlier invention, but the evidence allows only conjecture.[1] The watermill has been considered by many to have originated sometime between the 3rd and 1st centuries BC (Wikander 2008, 142), but evidence presented by M. J. T. Lewis (1997) suggests that it was most likely invented in Ptolemaic Alexandria around the mid-third century BC, in the context of the institutions founded by Ptolemy I to support technology and research (see also Wilson 2002). Most discussions of the waterwheel cannot help but quote Antipater, a name belonging to two contestants[2] for the following quote:

Do not put your hand to the millstone, you women grinders, slumber on, even if the cocks’ crowing announces the dawn. For Deo has assigned the nymphs to do the labor of your hands. And they, spurting to the top of the wheel, turn the axle that thanks to the curved spokes, moves the heavy, hollow millstones from Nisyros. Once again we enjoy the life of the first age, if we learn to feast on Deo’s fruits without labor. (cited in Bresson 2016, 197)

The colourful mix of mythology and utility make it stand out, and the emphasis on labour-saving is striking in that it has been alleged that the ancients did not care much for labour-saving devices due to the widespread slavery. More interesting, however, is the fact that Antipater does not see the watermill as leading to a departure from a past of toil and trouble, but a return to a past of “fruits without labour.” This contrasts starkly with the doctrine of progress that accompanied the inventions associated with the industrial revolution (Mumford 1934, 182-5).

Wikander points out that it makes sense that the waterwheel and watermill emerged to “provide for the needs of agricultural production,” given the pressures agriculture faced due to the period’s urbanization (2008, 140). Moreover, he writes that “the search for new power sources involved the two most energy-consuming agricultural activities: the lifting of water to irrigate otherwise uncultivable land and the grinding of flour” (2008, 140). The great advantages of the watermill led to its widespread adoption by the Romans as early as the first century AD (Wilson 2008a, 355).

What is it about the waterwheel that makes it a key breakthrough in energy technology? While human and animal muscles can perform a great deal of work, particularly when aided by machines providing mechanical advantage (pulleys, levers, etc.), our combined force cannot compete with that of steadily flowing streams of water. The waterwheel enables humans to tap into the kinetic energy of flowing water and convert it to rotational energy. This rotational energy can then be transferred directly or indirectly to various uses. How efficiently the kinetic energy of flowing water is transformed into useful work, such as the turning of a millstone, and the power capacity, depends on the type, design, material, etc. of the waterwheel. There are horizontal and vertical wheels, and the vertical waterwheels are divided into “undershot,” “breastshot,” and “overshot” types, depending on where the water hits the wheel.

The horizontal waterwheel can drive a millstone directly, but the vertical waterwheel requires right angle gears to transfer the vertical rotation of the wheel to the horizontal rotation of a millstone. Right angle gears are thought to have been invented in the first half of the 3rd century BC, also in Alexandria (Lewis 1993; Wikander 2008, 142). The choice of wheel type would depend on local circumstances, such as the speed of the stream and the nature of the work to be performed, but overshot wheels are overall significantly more efficient than most breast- and undershot wheels (Smil 2018, 149-52).

The waterwheel not only increased the energy available to perform work, but also began a transition in the qualitative nature of work. Mumford discusses this transition as part of “the eotechnic economy,” a phase in his periodization of modern technics, but it is more accurately seen as the result of the invention of harnessing water power through the waterwheel:

At the bottom of the eotechnic economy stands one important fact: the diminished use of human beings as prime movers, and the separation of the production of energy from its application and immediate control. While the tool still dominated production energy and human skill were united within the craftsman himself: with the separation of these two elements the productive process itself tended toward a greater impersonality… (Mumford 1934, 112)

This “substitution of inanimate for animate sources of power” is among the three principles that David S. Landes lists as characterizing the technological innovations that ushered in the Industrial Revolution (2003, 41). Up to this point, fire had been harnessed to change organic and inorganic materials and provide hospitable temperatures, the earth had been mastered increasingly since the agricultural revolution, wind had been harnessed for transportation, and water had been regulated to serve agriculture, but none of these major breakthroughs had yet made available mechanical power to replace musculature in the processes of production. The watermill did this, and it was not until the invention of powerful steam engines that the power of the waterwheel found its match.

In the ancient world, the most widespread use of water power was to grind grain, but other uses have been documented or suggested. Documented uses of water power include powering sawmills and pestles, and suggested uses include driving trip-hammers, fulling stocks and bellows (Wikander 2008; Wilson 2008, 367). The evidence for the diversified use of the watermill only appears in Roman times, but “the apparent paradox that most ‘Greek’ technology is found in the Roman period” is not really a paradox, given that innovation and diffusion are two different things, the latter often occurring long after the former (Greene 2008a, 82).

To take grain grinding as an example, the advantages conferred by the watermill were substantial. Smil writes that a small watermill, “manned by fewer than 10 workers, would grind enough in a day (10 hours of milling) to feed some 3,500 people,” but that “hand milling would have required at least 250 laborers” (2018, 154). Compared to animal-powered mills, Andrew Wilson suggests that an over-shot watermill with one pair of millstones could grind as much as five or more donkey-mills (2002, 12). While watermills cost more at the outset than human or animal-powered mills, they made up for this with higher output and much lower operating costs (Wilson 2002, 12).

III.II The steam engine

Two names are particularly associated with the invention of the steam engine: Thomas Newcomen and James Watt. Those who delve a little deeper will mention the role played by figures such as Thomas Savery or Denys Papin (e.g. Basalla 1988, 92-7). There are those, however, that trace the development of the steam engine all the way back to the Hellenistic period, and attempt the impossible task of reconstructing its more than two millennia long trajectory. Mumford (1934, 159) and Russo (2005, 126) note this connection, but Robert H. Thurston (1895) and Cort MacLean Johns (2021) elaborate on it, the latter in great detail. Thurston most beautifully captures the implications of the steam engine’s long history:

While following the records and traditions which relate to the steam-engine, I propose to call attention to the fact that its history illustrates the very important truth: Great inventions are never, and great discoveries are seldom, thework of any one mind. Every great invention is really either an aggregation of minor inventions, or the final step of a progression. It is not a creation, but a growth—as truly so as is that of the trees in the forest. Hence, the same invention is frequently brought out in several countries, and by several individuals, simultaneously. Frequently an important invention is made before the world is ready to receive it, and the unhappy inventor is taught, by his failure, that it is as unfortunate to be in advance of his age as to be behind it. Inventions only become successful when they are not only needed, but when mankind is so far advanced in intelligence as to appreciate and to express the necessity for them, and to at once make use of them. (Thurston 1895, 3, emphasis in original)

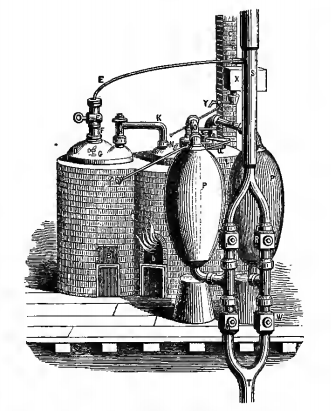

If the great invention of the modern steam engine is in fact a growth, as truly as a tree, it would be helpful to construct its development almost as one would a family tree. The word limit does not allow us to go into much textual detail, but the use of illustrations may be just as effective in portraying the evolution of the steam engine. Here, then, is a rough and selective visual genealogy of the steam engine, as it appears in the “Western” world:

Figure 1. Ctesibius’ (fl. 270 BC) water pump, from Heron’s Pneumatica. The raising of one piston sucks water in at the bottom, the lowering of the other pushes water into the ascending exit tube. Non-return valves ensure that the water flows only in the designated direction. Source: Russo 2005, 136.

Figure 2. Hero’s (fl. 62 AD) door-opening mechanism. Hot air from the altar expands and enters the sphere and pushes water from the sphere into the bucket, the weight of which opens the temple doors. Source: Thurston 1895, 6.

Figure 3. Hero’s Aeolipile. Steam enters the sphere from the side tubes and exits through two opposite outlet tubes placed tangentially, causing the sphere to spin. Source: Russo 2005, 136.

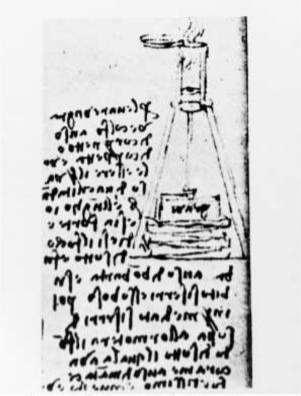

Figure 4. Leonardo DaVinci’s instrument for measuring the expanding volume of steam (1510). The counterweight N equals the weight of the piston so that that its weight does not disturb the measurement. Source: Johns 2021, 243.

Figure 5. Leonardo DaVinci’s device to use vacuum to lift weights (1504-9). An explosion in the cylinder would push the air out of it, it would then be sealed, thus creating a partial vacuum, which would then lift the “piston” and by extension the weight attached to it. Source: Johns 2021, 245.

Figure 6. Giovanni Battista della Porta’s steam pump (1601). Steam rises from the boiler and into the sealed container with water, the pressure created forces the water out of a pipe. Differs only from part of Hero’s door-opening device in that Porta uses steam and Hero hot air. Source: Thurston 1895, 14.

Figure 7. Jerónimo de Ayanz’s steam pump (1606).Steam alternately enters two containers and its pressure pushes the water out through the exit pipes. Check valves ensure that the water and steam only flow in the designated direction. Source: Johns 2021, 266.

Figure 8. Edward Somerset, second Marquis of Worcester’s steam force and suction pump (1665). Steam is led into one container, forcing the water into the ascending exit pipe. The steam is then shut off, and the condensation of the steam creates a vacuum which sucks water up the pipe from below. The two containers suck and push alternately. Source: Thurston 1895, 22.

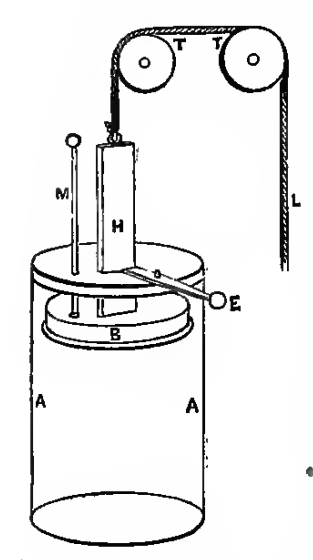

Figure 9. Christiaan Huygens’ explosion-vacuum engine (1680). An explosion in the cylinder drives the air out through non-return valves. The vacuum thus created pulls down the piston and carries the weight attached. Source: Thurston 1985, 26.

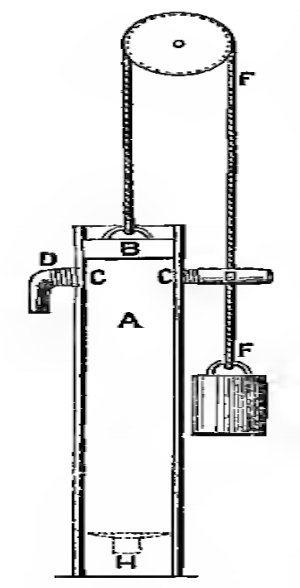

Figure 10. Denys Papin’s piston-cylinder steam engine (around 1690). Water at the bottom of the cylinder is turned into steam, pushing up the piston. The fire is then removed, the steam condenses, and the piston is pulled downwards, lifting the weight attached to the rope. As Thurston emphasizes, this is “the first steam-engine with a piston.” Source: Thurston 1985, 50.

Figure 11. Thomas Savery’s steam pump (1702). The first to enjoy some commercial success. Works like that of Worcester, but it has an additional boiler to supply stable steam pressure, and it spurts water on the surface of the containers to make the condensation of steam on the inside more rapid. Source: Thurston 1985, 37.

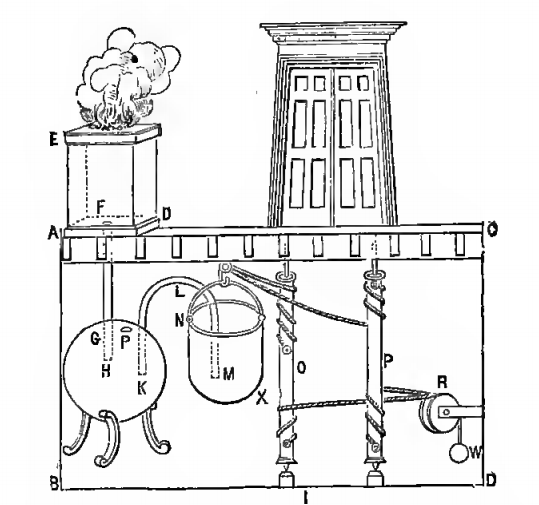

Figure 12. Thomas Newcomen’s “atmospheric” steam engine (1705). A breakthrough, widely adopted in British mines. Steam is let into the cylinder, and the piston is pulled up by the weight of the other end of the beam. A jet of water is then sent into the cylinder, causing the steam to rapidly condense, thereby creating a partial vacuum that pulls down the piston, which forces down the beam connected to the pump at the other side. Source: Thurston 1985, 59.

Thus, at the time that Newcomen created his steam engine, “every essential fact and every vital principle had been learned, and every one of the needed mechanical combinations had been successfully effected,” and his task was to put them together in new and effective way (Thurston 1895, 56). Despite its success in being widely adopted, the Newcomen engine suffered from very low efficiency in the conversion of heat to motor power, which stood initially at below 0.7% (Smil 2018, 217). The engine was later improved, changed, and put to other uses by the likes of James Watt and John Smeaton, but that is a story too long to enter into here (see Smil 2018, 235-45 and Thurston 1895).

While the history of the steam engine shows an evolution, the widespread adoption and improvement of the steam engine represents a revolution. By 1800, the average capacity of Watt and Boulton’s steam engines were at around 20 kW, five times the power of the typical watermill and almost three times the power of windmills (Smil 2018, 239). Moreover, the steam engine could be situated much more flexibly than the water- and windmill, and it ran steadily without the interruptions from unfavourable weather or wind.[3] Landes emphasizes the change to mineral fuels as being key, given that humans and animals required wheat, which was scarce, while the steam engine required coal, which in Britain was abundant (Landes 2003, 97). The use of fossil fuel also represented the first widespread converter of chemical energy into mechanical energy, “the first inanimate prime mover energized by fossil fuel rather than by an almost instant transformation of solar radiation” (Smil 2018, 235). Mumford puts it well:

… the large-scale opening up of coal seams meant that industry was beginning to live for the first time on an accumulation of potential energy, derived from the ferns of the carboniferous period, instead of upon current income. (1934, 157)

The increasingly effective exploitation of this “wealth” is indicated by the increased overall energy consumption. In England and Wales, the total energy consumption rose from about 117 Petajoules (PJ) in the 1650s to around 1 830 PJ in the 1850s, a roughly 15-fold increase (Smil 2018, 236). Beyond this, the steam engine was an agent of mechanization, furthering the process of substituting “machines – rapid, regular, precise, tireless – for human skill and effort” (Landes 2003, 41).

IV. The social world – economics and culture

In this section we will concentrate upon the social environment of technology in ancient Greece and industrializing Britain, in particular as it regards the waterwheel and the steam engine, but also in general.

IV.I Production and competition

In both Greece and Britain there was competitive production, competition for shares of domestic and international markets. In ancient Greece, Bresson writes that raw wool was an internationally traded commodity, “mass-produced in the pastureland zones of western Greece or Asia Minor,” then shipped to “large cities on the Aegean that specialized in textile production,” of which Athens was likely a major centre (Bresson 2016, 192-3). Britain produced its own wool, but as for cotton, the pattern just described applies largely to British import of raw cotton and export of finished textiles.

Intense competition is further illustrated by the keeping of trade secrets. For example, Attic vases (a key commodity at the time) were popular due to possible Athenian trade privileges, but “certainly also because of the superiority of their glaze, which was brilliant, lustrous, and hard: the secrets of its fabrication were long jealously guarded and were the key to a long-lasting success” (Bresson 2016, 211, emphasis added). A similar case is seen on Rhodes, where the punishment for spying on shipyards was death (Russo 2005, 116). The competition was commercial, in terms of market power, but also strategic, in terms of military technology, as the latter case likely represents.

Britain faced similar circumstances, although it most likely imposed less regulation of domestic competition than ancient Greek polities did, there being no equivalent of required trading spaces and the agoranomoi (market supervisors) that were common in Greek city-states (Bresson 2016, 239-50). In Britain too there was the kind of competition that led some inventors “to spend more time enforcing patent rights than earning them,” and industrial espionage was a common theme in Europe (Landes 2003, 64, 28; see also Musson and Robinson 1969, 393-426).

Compared to the world of ancient Greece, however, Britain had a larger home market and much larger foreign markets. Given the absence of internal customs and tolls, Britain constituted the largest “coherent market” in Europe in the 18th century (Landes 2003, 46). Moreover, Britain had access to vast overseas markets and colonies where it could obtain raw materials and export its finished products. In 1797-8, for example, the West Indies and American mainland colonies bought 57 per cent of English domestic exports (Landes 2003, 84). While Britain resembles classical Athens in the sense that they were both importers of raw fibres and exporters of textiles, the scale is different. By 1851, the British wool and cotton industries employed almost 450 000 workers (Landes 2003, 113), while the total number of people in Athens (citizens, foreigners, slaves) in the late 4th century BC is estimated at around 240 000 (Ober 2010, 280). This is a matter of degree (or scale), but as Landes writes: “questions of degree can often be decisive” (2003, 63).

There is a debate as to the relative importance of home and foreign markets in providing the demand that enabled the technological breakthroughs associated with the Industrial Revolution. Landes accords both some weight in explaining the “secularly expanding” demand for textiles that put pressures on the old cottage industry and putting out system (2003, 54-8). It is hard to say exactly how important demand of this sort is for the likelihood of technological innovation, as in many cases demand has not been met by invention, as Landes also points out. The large number of people employed in the industry no doubt also played a role, in that there was a large pool of potential inventors or innovators, who before complete mechanization were well aware of how the early machines worked and their shortcomings.

Demand might be considered as a factor that can “suggest” or “inspire” technological change if demand for certain products revealed shortcomings in the technologies used to produce them. This was the case with the steam engine and the innovations in the textile industry. High demand for coal revealed a shortcoming in the existing technology when the mines from which it was dug flooded, requiring considerable investments in animal power to lift water out of the mines. Savery’s engine tried to solve this problem, with only limited success. Newcomen’s steam engine succeeded brilliantly. It is important to emphasize the demand in and of itself is ineffectual; it can only play a role in technology if people think or believe that technological change is a possible, workable, and perhaps profitable way of satisfying demand.

Competition is a factor that can also suggest and inspire invention and innovation, but it will operate differently in different social contexts due to its intersubjective nature. The necessity of pumping water from mines is a physical reality that is brought forth by demand for coal, and there is therefore a playoff between the material aspect of the problem and its social expression. There is naturally a material element to competition (for sexual partners, scarce resources, etc.), but the type of competition in a socio-economic system is underdetermined by its material foundation.

The degree to which a system of production and exchange is competitive depends not only on how competitive one participant is or how competitive one participant believes another participant to be, but it depends also on the degree to which one participant believes that the average participant believes that participants in general are competitive.[4] With regards to technology, it will matter massively whether or not an economic system is comprised of participants that suspect or fear that others will outcompete them through technological innovation. As with demand, people’s beliefs about the possibility, feasibility, or necessity of technological improvement will affect which sectors or industries might be subject to technology-based competition. Past success will inspire further attempts, and in this way the process can become self-reinforcing.

The 18th century in Europe was rife with people who tried to outcompete each other technologically, and the textile and steam power industries offer examples. In 1741, Jacques de Vaucanson, a French inventor particularly famous for his automata, was appointed inspector of the silk manufacture in France by Cardinal Fleury because the French weaving industry was considered to have fallen behind that of Britain. Vaucanson, in carrying out his duties, invented in the mid to late 1740s a fully automated loom that could weave pre-programmed patterns, inspiring and anticipating the later Jacquard loom (Musée des Arts et Métiers 2021). As it was by far the most advanced weaving machine to date, it would have given France a critical advantage in its competition with Britain. However, it was not adopted, likely due to violent opposition from the weavers his machine would have replaced (Wood 2002).

Competition in the production of steam engines at the end of the 18th century is illustrated by the persistent competition Boulton and Watt faced in areas such as Lancashire. In a legal battle over infringements on Watt’s patent rights, two of the offenders asked if they could be granted licenses to make use of Watt’s inventions. He refused, as “it would be to all intents and purposes making them partners in the Patent and whetting a knife to cut our own throats” (cited in Musson and Robinson 1969, 420-1), indicating that Boulton and Watt’s technological edge was the sine qua non of their power in the competitive market.

There are analogous cases in ancient Greece, such as those mentioned earlier. Another example is the case of the Hellenistic “paper wars,” where Ptolemy II of Egypt forbade the export of papyrus to halt the growth of the Pergamene library, Alexandria’s main rival. Pergamum’s reaction was to develop an alternative writing material, parchment, made from animal skins, the term deriving from the Greek pergamene (Russo 2004, 248).

Despite the similarities, there are some notable differences. While ancient Greeks knew various machines, these were not used extensively in manufacture. As Andrew I. Wilson writes:

Greek and Roman machines were used primarily in construction, water-lifting, mining, the processing of agricultural produce, and warfare. The use of machines in manufacture was relatively limited, although … in the Roman and late Roman periods we find some evidence for the diversification of water-power for productive ends. (2008a, 337-8)

There is not yet evidence that water power was applied to so diverse industrial tasks as it was in the European Middle Ages and the early modern period (Musson and Robinson 1969, 67). Moreover, the traces of large-scale manufacturing in Antiquity (mainly Roman) are usually characterized by concentration of production and high division of labour, rather than any extensive use of mechanization and machines (Wilson 2008b). In this way there is a contrast with industrializing Britain, where machines for manufacturing were spreading rapidly and forcing producers to compete in terms of machine technology. With the rise of machine engineering and machine-producing partnerships and firms, there is a threshold crossed whereby humans not only compete with each other and with machines, but they also compete with each other through machines.

This type of machine-based competition cannot emerge without a requisite level and diffusion of mechanical and engineering skills, as well as availability and access to hard materials. In Britain, there had in the centuries before the industrial revolution been a considerable increase in mechanical skills and technology (Musson and Robinson 1969, 10-59), some imported and some home grown, and Britain’s output of pig iron rose more than sevenfold between 1740 and 1796 (Landes 2003, 96), thanks to the widespread substitution of coke for charcoal.

This, then, one can take to be a key difference. While the ancient Greeks had advanced machines, most notably the watermill, these did not become an integral part of the competitive productive system. In industrializing Britain, on the other hand, advanced machines were on the march to transform the economic system.

IV.II Royal patronage and investment

Part of an economic system are the public institutions that collect taxes and other revenues, and then use, invest, or waste them. Just as it makes a crucial difference whether the monied classes invest in production or political offices (Hudson 2010), so it a key question whether public institutions facilitate or hamper innovation.

The Hellenistic period offer some of the most conspicuous cases of fruitful royal patronage of arts and sciences. The most famous of these are the Library and the Mouseion (Museum) at Alexandria, which Ptolemy I established around 300 BC (Lewis 2000, 632). The Mouseion was a public research institution, and scholars were paid to work on many fields, such as mathematics, medicine, literature, technology, and so on. Lewis describes its effect as follows:

Alexandria in the third century was a place of intellectual ferment, and the spirit of enquiry was awakened here as never before. In the field of technology, it was responsible mainly for mechanical developments: simple gears, the cam and hence the trip hammer, pumps, the organ, water clocks with mechanisms, advanced automata, the scientific calibration of catapults, water-lifting devices and their close relative the vertical waterwheel. (2000, 633)

Despite the rivalry that existed between the Hellenistic kingdoms, there was also international cooperation among the various centres of research and innovation. For example, Philo of Byzantium and Archimedes of Syracuse both visited Alexandria, where they exchanged ideas and got inspiration. With regards to Philo, Serafina Cuomo writes:

Philo informs us about the existence of what we can call a network of catapult builders across Hellenistic kingdoms and cities, and he comments on the largesse and philotechnia (love of technical knowledge) of the Ptolemaic kings, thanks to whom particular progress had been made by the engineers in Alexandria. (2008, 22)

The Mouseion and Library of Alexandria were in effect a way that Ptolemy I diverted surplus – accumulated through taxes, booty, and other sources of public income – to maintaining large numbers of scholars, scientists, engineers, historians, scribes, etc. and to providing them with a larger collection of written texts than had ever been assembled. It was a large investment, but one that bore long-lasting fruits.

However effective at times, royal patronage has its drawbacks. Generous monarch, good harvests, peace and stability, taxes paid; these ensured that the likes of Archimedes were paid. If any of these fail, they might have to do their experiments part-time, or not at all. Archimedes, for example, died during the Roman attack on Syracuse, he was famously reputed to have been killed while carrying out calculations. In the second century BC, Ptolemy VIII “turned against the scholars,” causing “a brain drain from Alexandria just as abrupt as the earlier brain drain to it” (Lewis 2000, 633). Scientific and scholarly research at the mercy of a king is not merely at the mercy of his temper, but also at the mercy of his fortune in the palace and on the battlefield.

Another form of royal or public support of technology is patents, which have changed over time. An important development was the passing of the Statute of Monopolies by the English parliament in 1624. English monarchs had previously been able to issue patent monopolies to a wide range of industries, but this law restricted it sharply, yet making an exception for original inventions. This by no means gave people a right to a patent for their inventions, but it was now part of written law and could be granted. Written into law, it was more predictable than the fancy of individual monarchs. An English inventor could thus hope, not expect, to be rewarded for an invention. The debates on the effect of patent laws, on the industrial revolution for example, remain unresolved (Mokyr 2009).

IV.III Culture

We now turn to the difficult question of the relation of culture to technology. There are many ways to approach the issue, but there is only space to concentrate on a few of them. We will therefore only consider attitudes towards technology and the role of experimental science.

It has traditionally been held that the elites of Classical Greece and Rome had a negative and almost condescending view of utilitarian technology and its inventors and producers. This view has been most forcefully expressed by Moses I. Finley (1965; 1985). Thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, Seneca, etc. are considered representatives of this attitude. Aristotle, for example, wrote that

It is clear, therefore, that the young must be taught those of the useful arts that are absolutely necessary, but not all of them. It is obvious that the liberal arts should be kept separate from those that are not liberal, and that they must participate in such of the useful arts as will not make the participant vulgar … we term “banausic” those crafts that make the condition of the body worse, and the workshops where wages are earned, for they leave the mind preoccupied and debased.[5] (cited in Oleson 2008, 5)

More recent scholarship, however, has challenged this notion, point out that although these thinkers are representative of an attitude, it is by no means the only attitude, nor perhaps even the predominant attitude (Wilson 2002; Cuomo 2008; Greene 2008b). Evidence suggests that contrary opinions existed, some that even connected human technological ingenuity with the rise of civilization (Oleson 2008). The Hellenistic period, moreover, seems to differ from both its classical Greek predecessor and its Roman successor. Hero of Alexandria, for example, has an amusing passage showing the contrast:

The largest and most essential part of philosophical study is the one about tranquility [ataraxia], about which many researches have been made and still are being made by those who pursue learning; and I think research about tranquility will never reach an end through reasoning [logoi]. But mechanics has surpassed teaching through reasoning on this score and taught all human beings how to live a tranquil life by means of one of its branches, and the smallest – I mean, of course, the one concerning the so-called construction of artillery. By means of it, when in a state of peace, they will never be troubled by reason of resurgences of adversaries and enemies, nor, when war is upon them, will they ever be troubled by reason of the philosophy which it provides through its engines.[6] (cited in Cuomo 2008, 24-5)

In this regard, the Hellenistic scientists and engineers resemble much more their counterparts in modern Europe, such as Bacon, Galileo, Huygens, etc., than the Greek and Roman philosophers known to history. This holds the key to understanding a fundamental aspect of the different attitudes towards technology in these societies. Classical Greek philosophy was, in a way, “speculative” or theoretical (not in any derogatory sense). Much of it was concerned with ethical, political, epistemological, and ontological questions, whose answers were generally sought in philosophical discussion, i.e. dialectics.

On the other hand, Hellenistic and modern science, or “natural philosophy,” were marked by a greater concern with nature and her laws. Moreover, truth and evidence were not now to be sought in philosophical debate, but in nature herself as discovered and shown through experiments. While Mumford is right to emphasize the importance of the experimental method, he is wrong to call it an invention of early modern Europe. The experimental method was alive and breathing in the Hellenistic period, and some of the leading scientists of modern Europe took inspiration from the Hellenistic scientific heritage (Russo 2004, 229-60). Now, what is the relation of experimental science to technology? The answer is provided by Joseph Williamson, president of the Royal Society in the late 1670s: “…all Natural Knowledge was Originally produced (and still eminently depends) upon experiments, and all or most Experiments are couched among the Handy-crafts…” (quoted in Musson and Robinson 1969, 22, emphasis added).

This is the heart of the matter: experimental science depends on technology. The more advanced tools, instruments, machines, the further experimental science can proceed. A. R. Hall wrote the following regarding the scientific progress between the time of Galileo and Newton:

The standards [in experimental science] prevailing about the time of Newton’s death (1727) were utterly different from those of the age of Galileo and Kepler. Although the drive behind this change came from the scientists it was largely made possible by the success of the instrument-makers who served their needs. (cited in Musson and Robinson 1969, 18)

The mechanic and the scientist have often been united in the same person, as in the case of Hero of Alexandria or James Watt. It seems, then, that experimental science can be a powerful stimulant of technological invention and change. It is worth emphasizing that the watermill most likely emerged in the Mecca of Hellenistic experimental science, Alexandria, and that the steam engine’s long history is filled with the footprints of many experimental scientists. Watt said the following of the inspiration he got from the chemist Joseph Black:

The knowledge upon various subjects which [Dr. Black] was pleased to communicate to me, and the correct modes of reasoning and of making experiments of which he set me the example, certainly conduced very much to facilitate the progress of my inventions… (cited in Mokyr 2005, 52)

Watt gave also credit to other “natural philosophers” for helping him discover ways to improve Newcomen’s steam engine (Mokyr 2005, 52).

While ancient Greece had seen many brilliant scientists and engineers, there occurred a palpable decline after the 3rd century BC. Russo (2004) is inclined to blame this on the Romans, while Lewis suggests that it might be that the “engine of technical innovation, having worked flat out through the heady days of the third century, simply ran out of steam” in the absence of large scale royal patronage (Lewis 2000, 634). In other words, the approach and the accumulated knowledge of the leading Greek scientists and engineers did not gain a sufficient foothold in either culture or institutions to withstand the political instability and other changes that were to beset the Hellenistic world with its conquest by the Romans.

In modern Europe, on the other hand, experimental science took a stronger foothold, for it was not confined to one group or class, but spread more widely. Musson and Robinson writes that in Britain, “Royal princes could sit at the feet of self-educated lecturers in science… great landowners like the Shelburnes and the Egertons discussed engineering and workshop practice with business-men and semi-literate artisans…” (1969, 59). This is a key point emphasized by Mokyr (2005) and Musson and Robinson (1969), namely that in Britain before and during the Industrial Revolution, scientists, engineers, and mechanics were – to an unprecedented degree – interacting with and supporting each other regardless of class, status, or even national divisions.

A final point must be added: the Baconian thrust of science towards utilitarian ends. While the dream of conquering nature “is one of the oldest that has flowed and ebbed in man’s mind” (Mumford 1934, 37), Francis Bacon gave the most forceful and influential call to use experimental science to further this dream. Along with others, such as Descartes, Campanella, Glanvill, etc., Bacon helped establish a “new order” that had the following characteristics: “the use of science for the advancement of technics, and the direction of technics toward the conquest of nature” (Mumford 1934, 57). Descartes thought that if “practical” sciences enabled us to understand the world around us, “we might also apply them,” like the crafts of artisans, “in the same way to all the uses to which they are adapted, and thus render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature.” In Bacon’s New Atlantis, there was to be a “Solomon’s House” with two galleries: one where “we place patterns and samples of all manner of the more rare and excellent inventions: in the other we place the statues of all principal Inventors” (cited in Mumford 1934, 56). As Mumford notes,

… there is little that is vague or fanciful in all these conjectures about the new role to be played by science and the machine. The general staff of science had worked out the strategy of the campaign long before the commanders in the field had developed a tactics capable of carrying out the attack in detail… The laboratories and technical museums of the twentieth century existed first as a thought in the mind of this philosophical courtier: nothing that we do or practice today would have surprised him. (1934, 57)

V. Technology and its transmission, the longue durée

So far, we have attempted to compare ancient Greece and industrializing Britain. Although such a comparison can yield important insights, it masks a long-term continuity. Ancient Greece and industrializing Britain are both part of the long history of technology, and the achievements of the former were not completely lost to the latter. In this respect, William Faulkner’s famous quote is appropriate: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” For as Malm (2013) and others point out, the industrial revolution, as it manifested itself in the textile industry, ran mainly on water power well into the 19th century. In other words, the wheels of the British textile industry were turned by improved versions of Hellenistic technology. For this reason, it is important to also take a long-term perspective in understanding the place of technology in the two periods.

Hellenistic science and technology emerged and flourished in part thanks to royal patronage, but two other factors are worth mentioning. First, the conquests of Alexander led to a cultural exchange as Greek elites encountered the cultural, scientific, and technological traditions of the newly conquered peoples. “Cross-fertilization of cultures proceeded as never before,” Lewis writes, as Greeks absorbed “such scientific and practical arts as Babylonian astronomy and mathematics and Egyptian surveying and water management” (Lewis 2000, 632). At the same time that the Greeks were learning from other cultures, they were also increasingly communicating with each other across large areas, as shown by the fact that the Greek written language, from “the Hellenistic period onward,” became “remarkably uniform across the circum-Mediterranean world from Afghanistan to southern Italy” (Clarysse and Vandorpe 2008, 718). Not only, then, was there learning from other cultures, but Greek as a lingua franca enabled what was learnt to be communicated across vast distances.

Second, Macedon’s conquests led to Ptolemy I gaining control of Egypt, which was not only a “bread basket,” but also a “papyrus basket.” In Egypt, papyrus was cheap, and it was the most common writing material. It was exported to Greece and Rome, where it was the most common writing material for longer works (Clarysse and Vandorpe 2008, 719). Ptolemy had gotten his hands on abundant means to knowledge production, and he put them to good use through the Library and the Mouseion. It is hard to say exactly how important this access to a cheap external storage material was, but it is likely that Ptolemy’s investments in research would have cost more and yielded less if he had been forced to import papyrus or produce the much more costly parchment.

The cheap access to writing materials meant that the research carried out was more likely to be cumulative, as later scholars could draw on earlier successes. The likes of Ctesibius and Philo could be read by Heron and Vitruvius, and their contemporaries and successors could thus access Ctesibius and Philo through them. Although the Hellenistic tradition did not recover during the Roman period, it was transmitted in part by Vitruvius, and some of its inventions survived and diffused across the empire, such as the watermill, Ctesibius’ force pump, and the hydraulic organ (Green 2008, 808). The Romans had their own technological achievements, notably in construction, but these are not our subject here. When the Roman Empire fell apart in the west, it was Byzantium and principally the Arabs that took on and brought forward the ancient philosophical, scientific, and technological heritage. This heritage was then later transmitted to Europe, where it helped spark the Renaissance.

The importance of storage technologies in these movements and transmissions of technological knowledge is obvious. The great translation movement of Greek works into Arabic under the Abbasid caliphate was greatly facilitated by the art of paper-making. Ehsan Masood wrote that “in China, papermaking might have been an art, in Baghdad it became an industry” (2009, 53). In Europe, the introduction and improvement of the printing press by Gutenberg in around 1440 contributed enormously to the spread of knowledge. Elizabeth Eisenstein (1979), for example, argues that the printing press was crucial in enabling the growth of science and technology in Europe. Printing in vernaculars also helped democratize knowledge production and consumption, thereby enabling what might have remained an elite phenomenon to spread to a wider part of the population.

In this respect, it is interesting to note the connection between the translation and publication of Hero’s Pneumatics in Italy in 1575, which contains devices using steam and vacuum, and the subsequent research on vacuum and steam and their potential to do work (Mumford 1934, 159). Here, the transmission of technological knowledge is important not in showing how things should be done, but in inspiring new ways to recombine or apply old technologies.

When it came to the import of knowledge, Britain was a master. During the 18th century, England was behind both Germany and France in terms of published scientific journals, but was ahead in “translations and abridgements” (Mokyr 2005, 74). In addition to this, Britain received many immigration waves of skilled artisans from the continent, such as German miners and Dutch clothiers. Thus, when Britain set upon the path that has become known as the industrial revolution, she could rely on technologies from countless cultures and periods: the watermill from the Hellenistic period, paper, the compass, printing, and gunpowder from China and the East (via Arabs and others), mining technics from Germany, textile technologies from Italy and the Netherlands, canal and glass technology from Italy, chemical technologies from France, and so on.

We have here emphasized the continuity of the history of technology, and the importance of storage technologies, such as papyrus, paper, and printing, in enabling the continuity and cumulative advance that has occurred over the past millennia. The many discussions of why this or that society or period “failed” to industrialize would benefit from the consideration that the first place to industrialize, Britain, did so on the back of a long and cumulative development. Mumford puts it rather more forcefully: “The notion that a handful of British inventors suddenly made the wheels hum in the eighteenth century is too crude even to dish up as a fairy tale to children” (1934, 108-9).

VI. Conclusions

While we have examined many factors that conduce to technological innovation and change, it is clear that we cannot draw any conclusive conclusions about their relative causal weight. The subject matter of this thesis is far too complex to tolerate any categorical overgeneralizations. What Landes wrote about his own analysis in The Unbound Prometheus largely applies to this thesis’s topic: “Such judgement is necessarily personal: it would be hard, I think, to find two historians who would agree across the board on the ’causes’ of the European economic advance” (2003, 14). The arguments presented in this thesis will be summarized, but the relative weight accorded to them is the personal judgement of this thesis’ author.

The inventions of the watermill and the steam engine were both described as important breakthroughs in energy technology. The contexts of their emergence were both marked by a clear need, where the inventions proved crucial in satisfying that need. The watermill vastly reduced the labour necessary for water-lifting and grinding grains, and the Newcomen steam engine helped solve the problem of flooded mines. However, none of these problems were new to either period, they had beset earlier people and societies. The problem-solution explanation, therefore, is inadequate to account for the inventions. We have therefore explored other factors, notably the social environment in which the inventions emerged.

In examining economic factors, we have seen how demand and competition can play a role in stimulating innovation. Economic competition, in particular, seems to be a particularly powerful force when coupled with machine production. Capitalism coupled with machine production has been among the most powerful alliances in social history, and Mumford’s judgement seems appropriate when he writes that “the machine has suffered for the sins of capitalism; contrariwise, capitalism has often taken credit for the virtues of the machine” (1934, 27). We also saw how important royal patronage could be in fostering technological growth, and it is clear that rather than disappearing, it has merely metamorphosed into contemporary governments’ patent laws and spending on education, research, and innovation.

The discussion of culture looked at the attitudes towards technology in ancient Greece, and we argued that these were not uniform. Moreover, we suggested that the greater appreciation of technology in the Hellenistic period was due to the fact that experimental science had emerged there, and experimental science depends on technology. In this regard, it was argued that the Hellenistic scientists and engineers were similar to their counterparts in early modern Europe. A crucial difference, however, was that experimental science became a more deeply rooted and widespread phenomenon in Europe and Britain than it ever did in ancient Greece. We added to this the Baconian thrust of science towards utilitarian ends. While experimental science in itself can stimulate technological development, as it did in the Hellenistic period, its broad base in Europe and Britain, coupled with its Baconian thrust, made it an extremely powerful force for technological change and innovation, perhaps the most powerful force.

Finally, we left behind the comparative perspective, and adopted the longue durée view of technological development. Here, we noted that Britain’s foremost industry during the industrial revolution, the textile industry, went through its first decades of revolutionary expansion thanks to the power provided by watermill technology from the Hellenistic period. We then looked at the cultural exchanges in the wake of Macedon’s vast conquests, and how this enriched what was to become the Hellenistic heritage, written in a Greek language understood from southern Italy to Afghanistan. We also examined the importance of writing and storage technologies in facilitating cumulative advances, within ancient Greece, but also across time and space all the way to the Renaissance. In this regard, the printing press was noted as a crucial agent in spreading and democratizing access to knowledge in Europe, enabling experimental science to reach countless more minds than papyrus rolls ever could. Lastly, we saw how Britain was a master of learning from other countries, importing both foreign texts and people, so that when she began to industrialize, she could draw on the achievements of others.

Of all these factors, two factors stand out as the most powerful stimulants of technological innovation and change. These are machine-based competitive production and Baconian experimental science. Furthermore, one factor stands out as the most important enabler of technological innovation and change, namely cheap writing materials.

A thesis such as this one is difficult to conclude. In many ways, the loose ends left by this text are more interesting than the woven patterns, and it would require a much lengthier work to develop the above arguments fully and trace their implications in detail.

[1] John Peter Oleson (2000, 235) speculates that the waterwheel for water-lifting may have been the work of “some rural genius” in Egypt in the late 4th century BC, while Andrew I. Wilson (2002, 8) suggests that it may have emerged in the context of the Ptolemaic policy to reclaim and irrigate new land in the Fayum in the 3rd century BC.

[2] One lived at the end of the 2nd century and early 1st century BC, while the other lived in the Augustan period (Bresson 2016, 197).

[3] Its locational flexibility and temporal reliability led, as Malm (2013) documents, to its adoption in the textile industry before it became more powerful and cheaper than water power from a waterwheel. Capitalists seeking cheap labour could place their steam-powered factories in the middle of towns, and when the legislation imposed limits on the length of the working day, the steam engines could simply be made to work faster, the workers being forced to keep up with the machines (Malm 2013).

[4] This is essentially the same as what John Maynard Keynes wrote regarding investor behaviour: “We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be” (cited in Best 2004, 388).

[5] This resembles Adam Smith’s concern about the negative effects of the division of labour (1986/1776, 368-9).

[6] Here, Philo fits snugly into a later “tradition” of inventors that promise peace through instruments of war (Susskind 2018, 20-1).

VII. Bibliography

Basalla, George. 1988. The Evolution of Technology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berlin, Isaiah. 1972. “The Bent Twig: A Note on Nationalism.” Foreign Affairs 51 (1): 11-30.

Best, Jacqueline. 2004. “Hollowing out Keynesian Norms: how the search for a technical fix undermined the Bretton Woods Regime.” Review of International Studies, 30 (3): 383-404.

Bresson, Alain. 2016. The Making of the Ancient Greek Economy: Institutions, Markets, and Growth in the City-States. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Clarysse, Willy, and Katelijn Vandorpe. 2008. “Information Technologies: Writing, Book Production, and the Role of Literacy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 715-739. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cuomo, Serafina. 2008. “Ancient Written Sources for Engineering and Technology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 15-34. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eisenstein, Elizabeth. 1979. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

European Union. 2021. “Research & innovation.” Accessed 23.08.2021. https://europa.eu/european-union/topics/research-innovation_en.

Finley, Moses I. 1965. “Technical innovation and economic progress in the ancient world.” Economic History Review, 2nd ser., XVIII: 29-45.

Finley, Moses I. 1985. The Ancient Economy (2nd edition). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Frey, Carl Benedikt. 2019. The Technology Trap: Capital, Labour, and Power in the Age of Automation. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Greene, Kevin. 2008a. “Historiography and Theoretical Approaches.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 62-90. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Greene, Kevin. 2008b. “Inventors, Invention, and Attitudes toward Innovation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 800-818. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harari, Yuval Noah. 2014. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Signal Books.

Hudson, Michael. 2010. “Entrepreneurs: From the Near Eastern Takeoff to the Roman Collapse.” In The Invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship From Ancient Mesopotamia to Modern Times, edited by David S. Landes, Joel Mokyr, and William J. Baumol. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Johns, Cort MacLean. 2021. Industrial Revolutions: From Ctesibius to Mars. Pumbo.

Landes, David S. 2003/1969. The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis, M. J. T. 1993. “Gearing in the ancient world.” Endeavour, New Series, 17, no. 3: 110-115.

Lewis, M. J. T. 1997. Millstone and Hammer: The Origins of Water-Power. Hull: Hull University Press.

Lewis, M. J. T. 2000. “The Hellenistic Period.” In Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, edited by Örjan Wikander, 631-648. Leiden: Brill.

Malm, Andreas. 2013. “The Origins of Fossil Capital: From Water to Steam in the British Cotton Industry.” Historical Materialism 21 (1): 15-68.

Masood, Ehsan. 2009. Science and Islam, A History. London: Icon Books.

Mokyr, Joel. 2005. The Gifts of Athena: Historical Origins of the Knowledge Economy. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Mumford, Lewis. 1934. Technics and Civilization. London: George Routledge & Sons.

Musée des Arts et Métiers. 2021. “Métier à tisser les étoffes façonnées de Vaucanson destiné à remplacer l’ancien métier à la tire.” Accessed 17th of August, 2021. https://www.arts-et-metiers.net/musee/metier-tisser-les-etoffes-faconnees-de-vaucanson-destine-remplacer-lancien-metier-la-tire.

Musson, A. E. 1972. “Editor’s Introduction.” In Science, Technology, and Economic Growth in the Eighteenth Century. London: Methuen & co. ltd.

Musson, A. E. and Eric Robinson. 1969. Science and Technology in the Industrial Revolution. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Ober, Josiah. 2010. “Wealthy Hellas.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-) 140 (2): 241-86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40890980.

Oleson, John Peter. 2000. “Water Lifting.” In Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, edited by Örjan Wikander, 217-302. Leiden: Brill.

Oleson, John Peter. 2008. “Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 3-11. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Örjan, Wikander. 2008. “Sources of Energy and Exploitation of Power.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 136-157. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pope, Alexander. 1899/1734. Essay on Man. London: Macmillan and co., ltd.

Russo, Lucio. 2004. The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BC and Why It Had to Be Reborn. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Smil, Vaclav. 2018. Energy and Civilization: A History. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Smith, Adam. 1986/1776. The Wealth of Nations, Books I-III. London: Penguin Books.

Stevens, Yvonne A. 2016. “The Future: Innovation and Jobs.” Jurimetrics 56 (4): 367-85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26322685.

Susskind, Jamie. 2018. Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thurston, Robert H. 1895. A History of the Growth of the Steam-Engine. 5th edition. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & co. ltd. Digitalized by the Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/cu31924015355682/mode/2up.

Whitehead, Alfred N. 1997. “The Aims of Education.” In Education: Ends and Means, edited by Julius A. Sigler. University Press of America.

Wilson, Andrew I. 2002. “Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy.” The Journal of Roman Studies 92: 1-32. DOI:10.2307/3184857.

Wilson, Andrew I. 2008a. “Machines in Greek and Roman Technology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 337-366. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, Andrew I. 2008b. “Large-Scale Manufacturing, Standardization, and Trade.” In The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, edited by John Peter Oleson, 393-417. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wood, Gaby. 2002. Edison’s Eve: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.